The Scientific Revolution

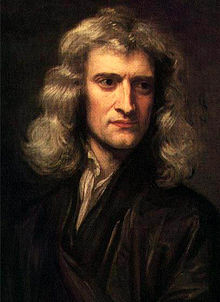

Isaac Newton

(1642-1727)

The most influential scientist

who ever lived

Godfrey Kneller's 1689 portrait of Isaac Newton (age 46)

Scientific Revolution

Adapted and compressed from 'A History of Europe' by Norman Davies, (Oxford) Chap VII

Recommended reading: Scientists of Faith

The same creative Spirit who was present when men desired to glorify God through the arts, appeared again when men turned their gaze to understand the order of God's glorious creation. The Scientific Revolution, generally held to have taken place between the mid-16th and the mid-17th centuries, has been heralded as the most important event in world history since the death, burial and resurrection of Jesus. It followed a natural progression from Renaissance rejection of the Church's spiritual monopoly, to Protestant emphasis on Scripture-reading which stirred men to know the God of the Bible and all of His creation.

Its forte lay in astronomy, and in those sciences such as mathematics, optics and physics which were needed to collect and interpret astronomical data. The difficulty with the Scientific Revolution lies in the fact that its precepts did not accord with prevailing ideas and practices. The so-called 'age of Copernicus, Bacon and Galileo' is a misnomer since, in most respects this was still the age of the alchemists, the astrologers and the magicians. The pioneers were all men of faith, disinclined to impugn the Church, but nevertheless bold in their conviction that scientific truths could not only be fathomed but also corroborated by revelation from the Bible.

Copernicus

Born Mikolaj Kopernik in Poland in 1473, he was educated at various universities in medicine, Greek, mathematics as well as Canon Law. He proposed a system that states that the Sun, not the Earth, is at rest in the center of the Universe, with the other heavenly bodies, planets and stars, revolving around it in circular orbits. His theory was fully supported with observations, measurements and predictions, the mark of true science.

This heliocentric system was considered implausible not only by the Church steeped in Aristotelian tradition, but also by the vast majority of his contemporaries, and by most astronomers and natural philosophers until the middle of the seventeenth century. Notably its defenders included such outspoken believers as Johannes Kepler (1571 -1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564 - 1642). Strong theoretical underpinning for the Copernican theory was finally provided by Sir Isaac Newton's theory of universal gravitation (1687).

Galileo

The Dane Tycho Brahe was a strong opponent but his colleague in Prague, Kepler established the elliptical shape of planetary orbits and enunciated the laws of motion underlying Copernicus. It was, though, the Florentine Galileo, one of the first to avail himself of the telescope, who really brought Copernicus to the public attention. He was as rash as he was perceptive, defending his findings with scathing attacks on his opponents Biblical misconceptions, 'The astronomical language of the Bible', he suggested, 'was designed for the comprehension of the ignorant'. This earned him a summons to Rome and a papal admonition, initiating the myth that religion hindered the advance of science, whereas it was the revelation of God's ordered universe that emboldened scientists.

Francis Bacon

Significantly this view was held by Francis Bacon, one time Chancellor of England, and the father of scientific method. He proposed that knowledge should proceed by orderly and systematic experimentation, and by inductions based on experimental data. In this he boldly opposed the traditional inductive method, where knowledge could only be established by reference to certain accepted axioms sanctioned by the Church. This has its parellel today where the predominant 'God and science can't mix' religion dictates how experimental data should be interpreted and produces such nonsense as the evolution theory.

Bacon held that scientific research must be complementary to the study of the Bible. Science was to be kept compatible with Christian theology, 'the scientist becomes the priest of God's Book of Nature'. One of Bacon's ardent followers, Bishop John Wilkins of Chester, a founder member of the Royal Society at Gresham (1686), wrote for example, 'The inhabitants of other worlds are redeemed by the same means as we are, by the blood of Christ'.

René Descartes and Blaise Pascal

Possibly nothing better illustrates the futility of atheism than the contrast between the two brilliant Frenchmen of this period. Both philosophers with a mathematical bent, benefitting from the prevailing atmosphere of revelation, one, Descartes, antagonistic towards God, the other praising Him. Descartes is most associated with the uncompromising rationalist system named after him (Cartesianism). Having rejected every piece of information that came to him through his senses, he concluded 'cogito ergo sum', I think, therefore I am. What a crowning glory of achievement! According to him humans and animals were nothing more than complex machines.

Blaise Pascal, on the other hand contributed greatly to the pool of human knowledge and is credited with producing the first digital calculating machine. After writing, at the age of sixteen, groundbreaking treatises on geometric shapes and atmospheric pressure he continued to make important contributions in the fields of mathematics and physics.

At the age of twenty-six however, Pascal would embark on a spiritual journey that would possess his mind and occupy his soul until his tragic death at the young age of thirty-nine in 1662. During this period in his life, "Pascal the mathematician and physicist" would become "Pascal the apologist and philosopher." Though he never abandoned his scientific experiments, he nevertheless consecrated his work to the glory of God and began to focus his penetrating mind on philosophical and theological pursuits.

Isaac Newton

In England, an inner circle, led by Dr. Wilkins, formed an 'Invisible College' in Oxford during the Civil War. They formed the Royal Society for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, and their first meeting was addressed by the architect Christopher Wren. Their early membership included Isaac Newton.

Born on Christmas Day, 1642, Newton is clearly the most influential scientist who ever lived. His accomplishments in mathematics, optics, and physics laid the foundations for modern science and revolutionized the world.

As a mathematician, Newton invented integral calculus, and jointly with Leibnitz, differential calculus. He made a huge impact on theoretical astronomy. He defined the laws of motion and universal gravitation which he used to predict precisely the motions of stars, and the planets around the sun. Using his discoveries in optics Newton constructed the first reflecting telescope.

But despite all this Newton's writings about theology, especially Biblical prophecy and church history, are more numerous than his writings on mathematics and physics, containing over a million words devoted to theological matters and doctrine. He practised higher standards than many around him when it came to both religion and science.

Biographers emphasize that Newton's scrutiny of nature was directed almost exclusively to the knowledge of God, as opposed to the development of new technological products or other things that might increase pleasure or comfort. Science was pursued for what it could teach men about God, not for pleasure or convenience. He expressed his conviction that, 'It is the perfection of God's works that they are all done with the greatest simplicity. He is the God of order and not of confusion. And therefore as they that would understand the frame of the world must endeavour to reduce their knowledge to all possible simplicity...' .

He died in London on March 20, 1727 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, the first scientist to be accorded this honour. With Newton, modern science came of age and the example of the Royal Society radiated across Europe.

By the second half of the 17th century, Europe's leading thinkers were largely agreed on a mechanical view of the universe operating on principles analagous to clockwork. The Law's of Nature, whose secrets God was now revealing, reflected the precision with which God created the universe.

There was to be no more conflict between science and religion for almost two hundred years.